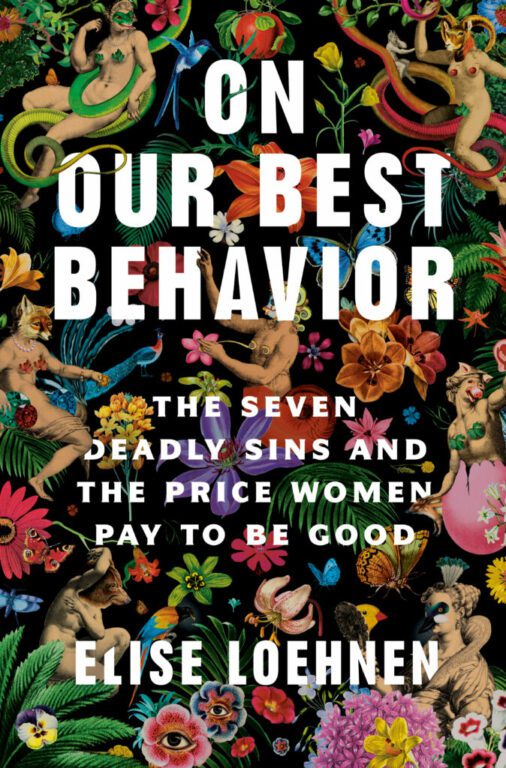

In her new book, On Our Best Behavior, Elise Loehnen doesn’t just shift the patriarchal paradigm, she shatters it. She transforms concepts from the Seven Deadly Sins into calls to action so that women can identify and own what they truly want to call into their lives. Recently, Elise sat down with Wanderlust to reflect on the deeply personal work required to break this cycle, and what being on her best behavior means to her now.

Wanderlust: You begin the book with a concept of people having a first and second nature, where who we are at our core can be at odds with how society informs that identity. In the chapter on pride, you discuss the “true self” versus the “illusion self.” You write, “We need to surrender to who we are and not who we think we should be.” How have you surrendered to who you are in your own life? How do you let your true self shine?

photo by Vanessa Tierney

Elise Loehnen: Through a lot of introspection and intervention—I’ve found that I’ve had to interrupt my own thinking, again and again, about who I am and how I’m supposed to behave. These voices in our head are insistent and loud. The great thing that I’ve observed as more and more people have read advanced copies of the book pre-pub is that once women start talking to each other about these concepts, it becomes much easier to identify them. This is deeply personal work, but it’s also work we need to do in community. The more I speak to other women about their anger, their envy, their gluttony, the more conscious and aware we all seem to become.

WL: In the chapter where you address sloth, you show how imperative it is for both our bodies and minds to have rest, pointing out that the conscious brain can process sixty bits per second, while the unconscious brain can process 11 million bits per second! What kinds of changes did you make when it comes to embracing rest? Where did you see the most improvements?

EL: It’s honestly been scary to embrace rest. I have allowed myself to watch more TV and take more naps in the last six months than I have in my whole life. I need rest. I am deeply, profoundly tired. But here’s the thing: the constant grind and busyness was killing me, literally bringing me to my knees. I couldn’t keep pushing in that same way. In this period of rest—deep rest—I’ve had to wrestle with all the fear it stokes about whether I’ll ever be able to “produce” at the same rate as before. I worry I’ve lost my drive. But in that process, I recognize that what I’ve called “drive” has really been a cattle prod of fear. And so, resisting this feels like an essential gate for me to walk through—to not say yes to every paying offer, to not rush to fill my days with things to-do. I feel close to being refreshed, close to being able to re-engage. But hopefully not at the same pace.

photo by Vanessa Tierney

WL: You give the reader a very complete picture—historical and religious context, scientific research, personal accounts, and current data—to show how deeply these codes of conduct permeate our lives. What findings surprised you most in your research for this book?

EL: Honestly, that the Seven Deadly Sins weren’t even in the Bible. That floored me, as I think most of us assume they are religious law, or that Jesus must have said them at some point. Nope! They’re the perfect example of how religion has become culture, how these things are passed down from generation to generation.

WL: What does being on your best behavior mean to you now? Of the Seven Deadly Sins, which were easy to strip away, and which were hardest to let go?

EL: On my best behavior now means being myself, even if that’s uncomfortable for other people or requires some shape-shifting within my family. I think Sloth is still the most insistent for me—this urge to be a “good mother” is intense. What I’ve found though, is that as I’ve moved past my instinct to do all the things for all the people, as I’ve put stuff down, my husband Rob has moved in to take over some of these duties. It’s interesting to see how our energy changes as roles and rules start to shift even without actually saying anything at all. If I don’t return the fieldtrip permission slip in the first ten minutes, and allow, gasp, HOURS, or even a day to pass, ROB DOES IT.

Honestly, they’ve all required a lot of work. I think Envy was the easiest for me to integrate—probably followed by Gluttony, because I’m just awfully tired of policing myself about food. WL: Each chapter is a radical act of reclaiming one’s space as an act of self-love. When talking about envy, you address the scarcity mentality that blocks us from actualizing our dreams. Instead of thinking “it’s her or me”, you shift it to “she has it, so I can have it too.” How important is it for us to make this shift?

WL: Each chapter is a radical act of reclaiming one’s space as an act of self-love. When talking about envy, you address the scarcity mentality that blocks us from actualizing our dreams. Instead of thinking “it’s her or me”, you shift it to “she has it, so I can have it too.” How important is it for us to make this shift?

EL: I think if there’s ONE THING that women get from this book, it’s this: Identify, diagnose, and own our wanting. We must then move past the fear of scarcity, the idea that only one of us, maybe two of us, can do the thing. Right now, we’re programmed to believe that if someone is doing what we want to be doing, we must dethrone her, that there’s not room for all of us. It is consistent and insidious and is the basis of our instinct to bat each other down or dismiss each other with statements like: “I just don’t like her,” “Who does she think she is?” and “She’s gotten too big for her britches.”

If we can stop policing each other’s self-expression and “bigness,” I think we can lean into our own. We’re at a point in time where it is essential that we all bring our gifts to bear.

—

Cameron Joy Machell is a writer and journalist covering yoga, travel, and wellness. Always planning her next adventure, she has chased the Northern Lights across Iceland, camped under the stars in the Sahara Desert, and sipped kava with chiefs in Fiji. When she’s not traveling, you can find her at home in New England, in the garden or on her mat.

Cameron Joy Machell is a writer and journalist covering yoga, travel, and wellness. Always planning her next adventure, she has chased the Northern Lights across Iceland, camped under the stars in the Sahara Desert, and sipped kava with chiefs in Fiji. When she’s not traveling, you can find her at home in New England, in the garden or on her mat.